After Harvard: The Fight Against Race-Based Admissions at the US Naval Academy

An in-depth investigation into race-based admissions at America’s elite military academies—and the landmark case that challenged them (and lost)

Table of Contents

Introduction and Background

The views expressed in this report are my own and do not reflect the views of any of the parties involved in the case or the institutions referenced. Where this report references materials from Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. U.S. Naval Academy (USNA), it does so solely on the basis of publicly available records from the case—most of which were downloaded via PACER. All cited documents can be accessed and downloaded here.

Race-conscious admissions are illegal in American universities—and, as of February 2025, are now banned at the institutions that train the nation’s military leaders. This dramatic shift followed President Donald Trump’s January 27, 2025, executive order prohibiting race- or sex-based preferences across the U.S. Armed Forces, and a subsequent directive by Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth enforcing those principles throughout the Department of Defense. In response, the Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy (USNA), Vice Admiral Yvette Davids, formally revised the Academy’s admissions policy on February 14, 2025. The new guidance prohibits consideration of race, ethnicity, or sex at any stage of the admissions process—a change confirmed in Senate testimony and a Department of Justice court filing.1

Although USNA has insisted that its use of race was “limited” and “non-determinative,” it also admitted to never having studied the impact of race on the composition of its admitted classes. Moreover, statistical analysis of admissions data tells a different story: a White applicant with a 5% chance of admission would have a 50% chance if evaluated as Black, and more than 70% of Black admits would not have been admitted under a race-neutral system. These findings, among similarly damning others examined in this report, directly contradict USNA’s characterization of its policies.

Nevertheless, Judge Richard Bennett ultimately ruled in favor of USNA on December 6, 2024, allowing race-based admissions to continue. His ruling effectively treated footnote 4 of the Supreme Court’s SFFA v. Harvard/UNC decision—which states that the ruling does not “address the propriety of race-based admissions [in the military academies]”—as a carve-out for service academies, shielding them from the Court’s holding and exempting them from the strict scrutiny standard applied to civilian universities. Accordingly, rather than applying the exacting strict scrutiny standard affirmed in Harvard, Bennett deferred entirely to the government’s assertions, accepting race-conscious admissions as essential to national security without demanding serious empirical proof.

Now, however, the policy defended in that decision has been rescinded. In light of the Academy’s revised guidance, the Department of Justice has moved to suspend appellate briefing while the parties consider whether the case has been rendered moot—and whether the district court’s ruling should be vacated. As of this writing, the case remains in legal limbo.

Yet even if the case is declared moot, its significance is far from extinguished. First, the risk of policy reversal under a future administration is real—if not inevitable. Without stronger institutional safeguards, nothing prevents a future Secretary of Defense—or Academy Superintendent—from reinstating race-based preferences. Second, if allowed to stand, the district court ruling sets a dangerous precedent: that other government agencies in a future administration may invoke vague claims of “national security” to justify racial classifications. The result would be a profound shift in equal protection jurisprudence, granting the executive branch a new and expansive justification for racial classifications in areas far beyond military personnel policy. Finally, the legal, empirical, and policy arguments advanced in SFFA v. USNA offer a critical lens for evaluating the proper role of merit, fairness, and equality in military officer selection.

About This Report

While the Supreme Court's 2023 decision in SFFA v. Harvard/UNC drew national attention to affirmative action in higher education, the application of race-conscious admissions policies at military academies has remained largely opaque—until now.

This report provides the first in-depth analysis of how racial preferences operate at a U.S. service academy. Focusing on SFFA v. USNA, it systematically examines the role of racial preferences in USNA’s admissions process and assesses their impact on the qualifications, performance, and eventual service assignments of admitted students. It also scrutinizes the legal and empirical justifications advanced by the government, including the claim that racial diversity is essential to military effectiveness.

In addition, the report critiques U.S. District Judge Richard Bennett’s December 2024 ruling, highlighting its deference to government assertions and its failure to apply meaningful constitutional scrutiny. Finally, it offers a series of policy recommendations—judicial, legislative, and executive—to ensure that the ban on racial preferences at service academies endures beyond the current Trump administration.

All told, this report not only brings long-overdue transparency to a system that has operated with minimal public scrutiny—it also lays a crucial foundation for preventing the quiet return of race-based preferences under future administrations. It is thus essential reading for policymakers, military leaders, legal scholars, and citizens concerned by the spread of racial equity-focused policies and norms in military institutions, as well as anyone interested in understanding how such policies have operated in practice, how they have been defended and justified, and how similar measures could resurface in the future.

Outline and Summary Overview of Report

This report is divided into five sections, each building upon the previous one to examine the role of racial preferences in USNA admissions, Judge Bennett’s ruling, and the broader legal and policy implications.

Section 1 provides an in-depth overview of USNA’s admissions process, which differs significantly from civilian universities due to its legally mandated nomination system and strict eligibility requirements. Unlike traditional colleges, USNA applicants must first secure a nomination—typically from a member of Congress—before they can be considered for admission. While USNA publicly maintains that race is not considered in most admissions decisions, the academy explicitly acknowledges its “limited” use in a variety of discretionary decisions, including the selection of Congressional slate winners, the awarding of Additional Appointee (AA) admissions, and the granting of Letters of Assurance (LOAs). By outlining the mechanics of the nomination and admissions process in detail, this section establishes the foundation for understanding how USNA exercises discretion in its admissions decisions and how that discretion creates opportunities for racial preferences.

Section 2 empirically assesses the extent to which race influences USNA’s admissions decisions. Using statistical analysis conducted by Duke University economist and SFFA expert witness Peter Arcidiacono, this section demonstrates that racial preferences play a decisive role in admission outcomes, directly contradicting USNA’s claims that racial considerations are limited and non-determinative. Admissions data reveal stark racial disparities, with non-White applicants—particularly Black applicants—admitted at significantly higher rates than White applicants with comparable WPM scores, especially in the middle qualification deciles. Regression models controlling for a broad range of factors confirm that these disparities persist even after accounting for potential omitted variables. Arcidiacono’s analysis also reveals how racial preferences extend beyond direct admissions into indirect pathways, particularly the Naval Academy Preparatory School (NAPS), where Black applicants are admitted at disproportionately high rates and whose matriculants enjoy near-automatic acceptance into USNA the following year. Additional discretionary mechanisms—including LOAs, medical waivers, and adjustments through the Recommendations of the Admissions Board (RAB)—further amplify racial preferences.

Beyond admissions, statistical analysis of matriculant performance data reveals that racial preferences at USNA have far-reaching consequences for academic performance, discipline, and graduation rates. Black midshipmen consistently earn lower grades, are more likely to be placed in remedial courses, and are significantly underrepresented on the Commandant’s List—a merit-based designation awarded to midshipmen with strong academic and leadership evaluations. Even after controlling for observable qualifications, racial disparities in performance persist, suggesting that Black applicants underperform relative to their admissions credentials and that the magnitude of racial preferences may be even larger than initially estimated. Further, internal USNA data reveal that Black midshipmen are overrepresented in conduct and honor offenses, underrepresented among the top Order of Merit (OOM) rankings, and disproportionately concentrated in the bottom OOM deciles. Minority midshipmen—except for Asians—also experience higher attrition and lower graduation rates than their White peers, with Black midshipmen typically graduating at rates 10 to 15 percentage points lower than Whites. These disparities persist despite USNA’s institutional shift toward a “developmental model” intended to boost overall graduation rates, raising serious concerns about whether racial preferences are setting some students up for failure rather than success. Taken together, these findings further undermine USNA’s claims that race is merely a minor, non-determinative factor in its admissions process.

Section 3 evaluates USNA’s defense of its race-conscious admissions practices, analyzing both its statistical rebuttal to Arcidiacono’s findings and its broader justification for racial preferences. The first part critiques USNA’s counteranalysis, which relied on the testimony of Dr. Stuart Gurrea, a legal economist with no peer-reviewed academic publications who was paid more than $500,000 in taxpayer money to challenge Arcidiacono’s findings. Rather than conducting an independent statistical analysis, Gurrea merely attempted to cast doubt on Arcidiacono’s methodology, arguing that the results were distorted by omitted variable bias, that Arcidiacono’s racial classification methods were flawed, and that logistic regression was an inappropriate tool for studying USNA admissions. However, these critiques fail under scrutiny. Not only do Gurrea’s arguments lack empirical support, but his suggested methodological changes, if taken seriously, would render USNA’s admissions process unmeasurable and immune to external scrutiny. That USNA relied on such a weak counteranalysis—rather than producing its own rigorous statistical study—suggests that it either could not refute Arcidiacono’s findings or feared what a full empirical investigation would reveal.

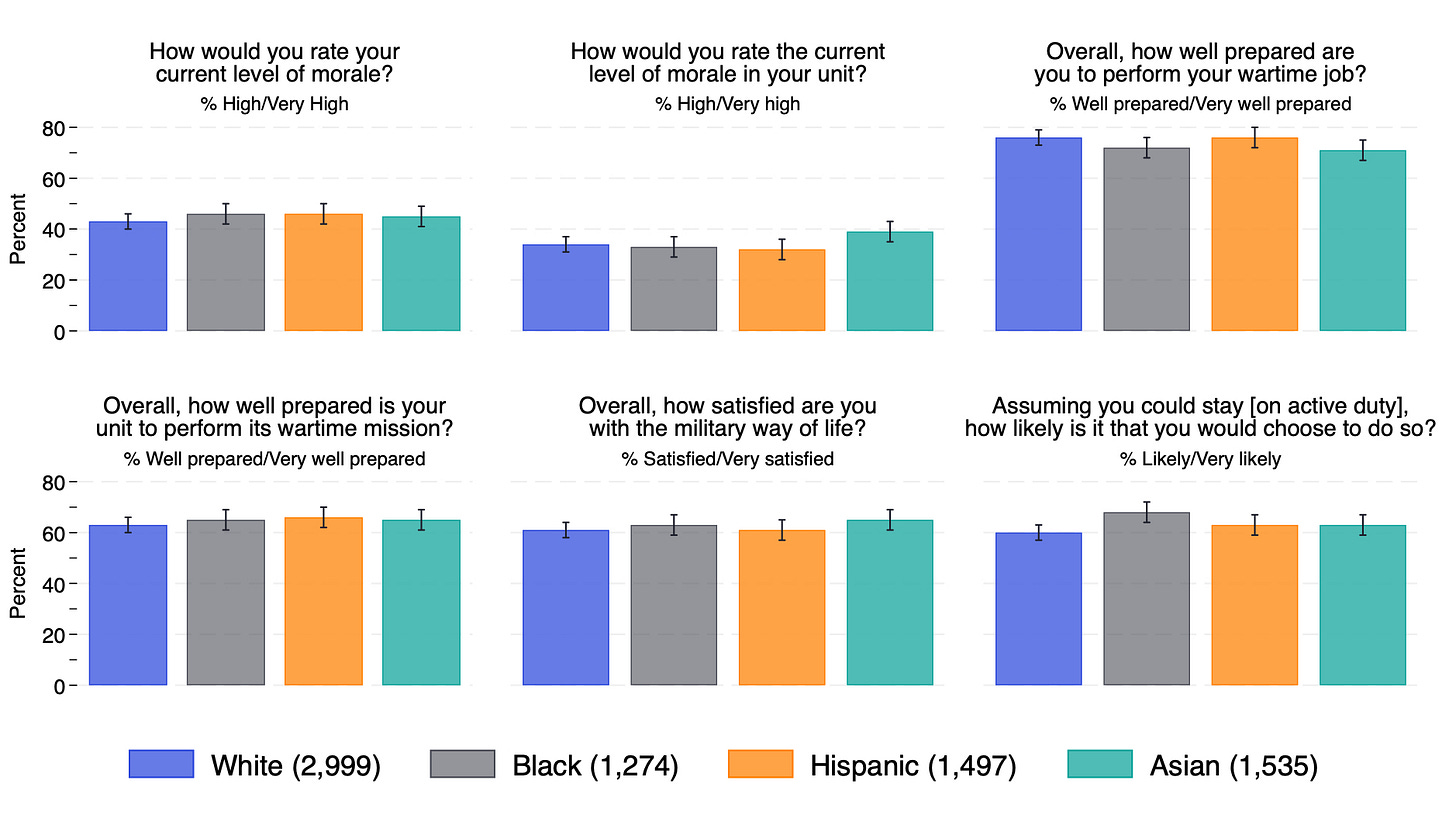

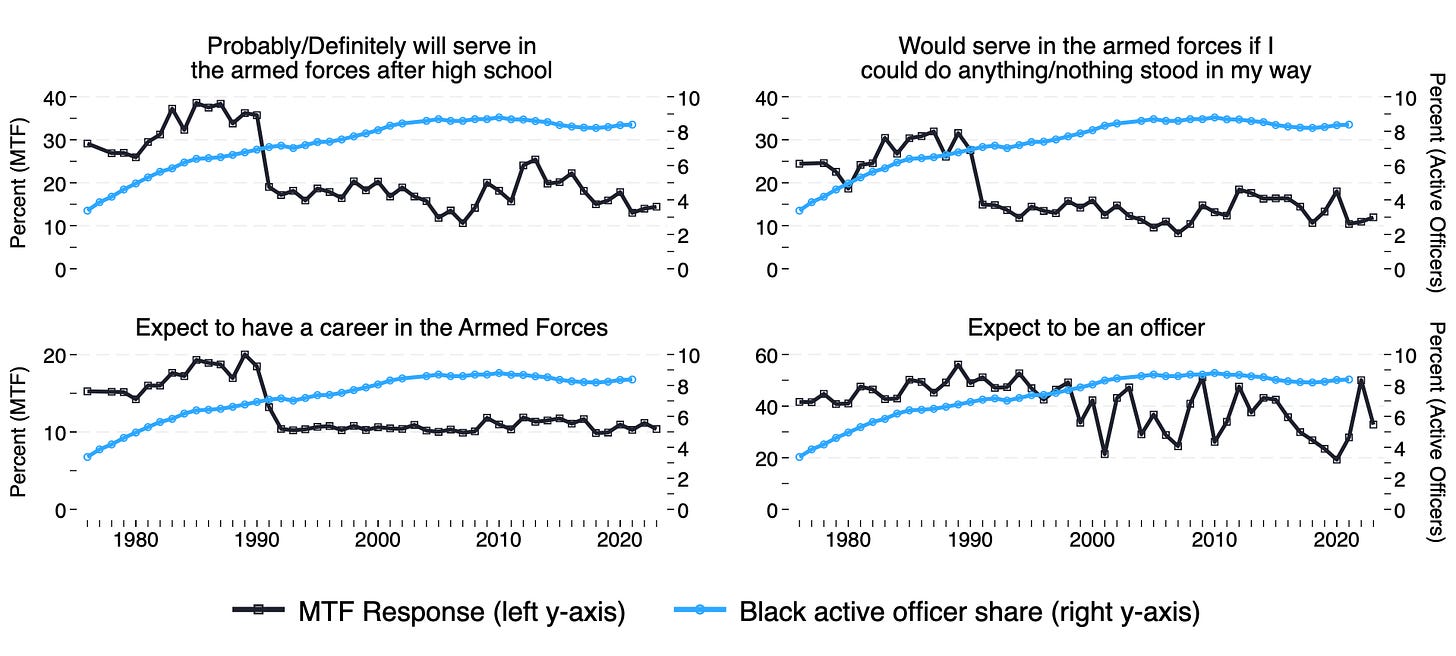

The second part of Section 3 shifts to USNA’s core legal defense, which hinges on the claim that racial diversity is essential for military effectiveness. Judge Bennett’s ruling largely accepts this assertion at face value, yet a closer examination—and even the government’s own testimony—reveals that the military has never conducted a systematic study proving that racial diversity improves battlefield performance, unit cohesion, or morale. A review of military diversity reports and testimony from military officials confirms that these justifications rest entirely on speculation rather than empirical evidence. Likewise, claims that increasing racial diversity in officer ranks is necessary to improve minority recruitment and retention lack empirical support. Historically, Black enlistment has remained strong regardless of the racial composition of the officer corps, and retention rates show no clear relationship to racial preferences. By critically assessing USNA’s diversity rationale, this section argues that it fails to meet the ‘compelling interest’ standard and is based more on untested assumptions than hard data.

Section 4 examines Judge Bennett’s ruling, arguing that it is not a neutral application of strict scrutiny but rather a legal justification designed to protect USNA’s race-conscious admissions policies. Unlike previous affirmative action rulings, which at least engaged with competing evidence, Bennett systematically defers to USNA, shifting the burden of proof onto SFFA and failing to demand clear empirical support for USNA’s claims. The first part critiques Bennett’s handling of the “compelling interest” standard, showing how he accepts USNA’s assertions about military diversity’s benefits without requiring concrete, measurable proof. Instead of engaging with the absence of empirical support, he relies on anecdotal testimony, politically motivated reports, and historical misrepresentations to justify his conclusions.

The second part of Section 4 examines how Bennett misapplies the standard of narrow tailoring. Instead of requiring USNA to exhaustively explore race-neutral alternatives, he dismisses them outright, applying an unconstitutional standard that requires such alternatives to precisely replicate current racial outcomes. His rejection of socioeconomic-based alternatives ignores clear evidence that such policies could maintain substantial racial diversity while expanding opportunities for disadvantaged applicants. Moreover, his justification for racial preferences as “time-limited” is illusory. By tying their continuation to an undefined future demographic balance, he effectively allows them to persist indefinitely, amounting to unconstitutional racial balancing. Beyond its immediate implications, Bennett’s ruling sets a dangerous precedent. If upheld, it would exempt military institutions from constitutional constraints on racial classifications, allowing them to justify racial preferences indefinitely under the guise of national security.

Section 5 outlines a comprehensive, three-pronged strategy—judicial, legislative, and executive—for ensuring that race-based admissions at USNA and other service academies are permanently eliminated and not quietly reinstated under future administrations. While the USNA case is now in legal limbo following the Academy’s policy reversal, judicial options remain crucial: parallel litigation at West Point and the Air Force Academy still offers a path to definitive constitutional resolution. However, SFFA must resist efforts to moot any of these cases absent structural safeguards. If mootness is ultimately declared, it must seek vacatur of the Bennett’s district court ruling to ensure it carries no precedential weight.

On the legislative front, embedding a statutory ban within the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) would offer more durable protections than executive orders alone, especially if pursued with active support from the Trump administration. Meanwhile, executive action provides immediate tools for enforcement, transparency, and deeper structural reform. These include auditing and data disclosure requirements to ensure compliance with the new ban, and the creation of an independent commission to reexamine the military’s longstanding but empirically untested “diversity rationale.” Finally, the section recommends strategically linking the admissions ban to the commission’s work by framing the policy as a temporary suspension pending evidence review. This approach would reframe the debate in empirical terms, shift the burden of proof onto proponents of racial preferences, and build institutional and legal barriers to their return. Taken together, these recommendations form a robust blueprint for securing the permanent end of race-conscious admissions at the service academies.

1. Understanding USNA Admissions

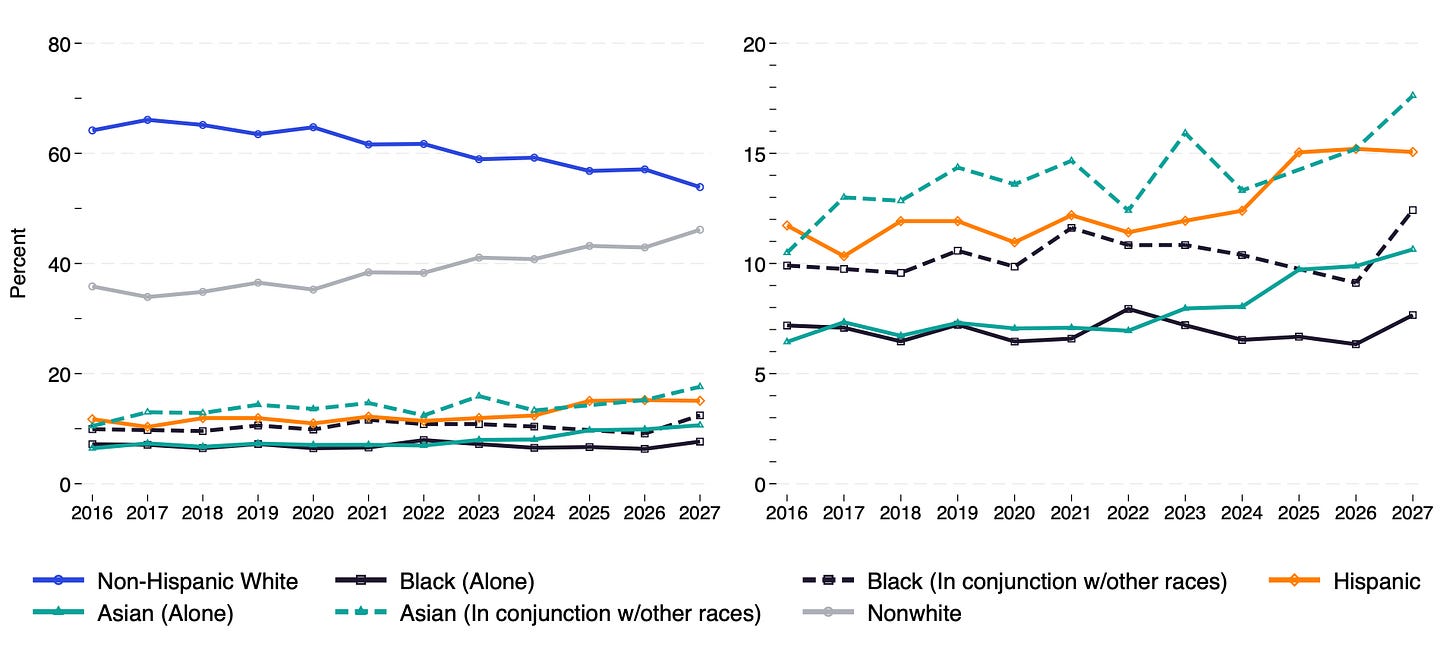

For clarity, references in this report to the 2023–2027 admissions cycles correspond to students who matriculated into the USNA Classes of 2023 through 2027. Since candidates apply nearly a year before matriculating, these admission cycles roughly align with applications submitted between 2018 and 2022. For example, an applicant who applied in 2018 and was accepted would have matriculated into the Class of 2023, while an applicant who applied in 2022 would belong to the Class of 2027. This distinction is important when interpreting data throughout the report.

1.1 Initial Application and Eligibility Requirements

Applying to the U.S. Naval Academy (USNA) differs significantly from applying to traditional universities. As early as their junior year of high school, prospective candidates must complete a preliminary application, which serves as an initial screening tool to ensure they meet USNA’s minimum eligibility requirements. These include age (17–22 years), U.S. citizenship (with a valid Social Security number), marital status (unmarried), dependency status (no dependents), and pregnancy status (not pregnant).2

Candidates who pass this initial stage proceed to the formal application process, which includes written essays (e.g., personal statements), letters of recommendation, and evaluations from high school guidance counselors. These evaluations provide information on a candidate’s GPA, class rank, and whether they are classified as “disadvantaged” or of a “minority” background.3

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, USNA required applicants to submit standardized test scores (SAT or ACT). However, for the Classes of 2025–2027, it adopted a “test-flexible” policy, which it has since discontinued.4

Beyond academic qualifications, applicants must also pass a medical examination, complete the Candidate Fitness Assessment (CFA), and participate in an interview with a Blue and Gold Officer (BGO)—all of which must be completed by January 31 of their senior year.

1.2 The Whole Person Multiple (WPM) and Candidate Evaluations

Once an applicant’s file is submitted, it is evaluated using the Whole Person Multiple (WPM) score, a composite metric calculated through an algorithm based on USNA’s weighting formula. Before the class of 2025 admissions cycle, the WPM score was determined by an applicant’s highest SAT math and verbal scores, high school class rank, rankings of athletic and non-athletic extracurricular activities, and character-related appraisals from math and English teachers (e.g., “Makes friends easily”). However, after adopting its “test-flexible” policy, USNA removed standardized test scores from the WPM calculation, redistributing their weight to class rank and extracurricular activities.5

A more subjective element of the WPM is the Recommendations of the Admissions Board (RAB), which allows the admissions board to adjust an applicant’s raw WPM score by up to ±9,000 points, with any adjustment beyond that requiring approval from the Dean of Admissions.6 Factors influencing RAB adjustments include unusual life experiences, hardship, the quality of the Blue and Gold Officer (BGO) interview, participation in Advanced Placement (AP) courses, personal statements, extracurricular involvement, and character assessments. These adjustments are voted on by the admissions board and take effect with majority approval. For the admissions cycles spanning 2023–2027, the average applicant received a net adjustment of +2,450 points (standard deviation = 1,870).7

WPM scores generally range from 40,000 to 80,000 points.8 Applicants for the class years 2023–2027 averaged raw WPM scores of 66,580 (standard deviation = 6,370).9 Scores of 70,000 or higher are considered “highly qualified” and eligible for early appointment offers. While a score of 58,000 is the general minimum for qualification, exceptions may be made for candidates with exceptional qualifications, graduates of schools with high college admission rates, or individuals with unique experiences or accomplishments.10

The WPM is designed “to assist in predicting first-year success at the Naval Academy as well as comparing candidates when being considered for offers of appointment from official nomination sources.”11 Notably, USNA maintains that an applicant’s racial or ethnic background is neither considered in the calculation of WPM scores nor in RAB adjustments.12

1.3 The Nomination Process

1.3.1 Congressional Nominations

One of the most distinctive aspects of the USNA application process is the requirement to secure a nomination from an official source. The most common category is congressional nominations, which account for more than 80% of USNA’s admitted class.13 These nominations are granted by the Vice President, Members of Congress, Delegates to Congress representing Washington, D.C., and U.S. territories, as well as the Governor and Resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico.

Each member of Congress is allocated five nomination “charges”—or admission slots—at USNA at any given time.14 When a nominee is admitted, they are “charged” to that member. Members with fewer than five charges at the end of an academic year are considered to have a “vacancy,” allowing them to nominate new candidates. Typically, members have one vacancy per year and may nominate up to 10 candidates for each vacancy, all of whom must reside in the member’s district or state.

Members of Congress may submit their nominations using one of three methods.15 The most common approach, used by approximately 65% of members, is the competitive method, in which a member submits a slate of up to 10 nominees without ranking them in order of preference. USNA then evaluates and ranks these nominees based on their Whole Person Multiple (WPM) scores, with the highest-scoring qualified candidate expected to receive the appointment. However, USNA retains some flexibility in this process. If the second-highest candidate is within 4,000 WPM points of the top candidate, the Slate Review Committee (SRC) may choose the lower-scoring nominee instead.16 Importantly, USNA acknowledges that in such cases, race or ethnicity “may be one of numerous factors” in determining the slate winner.17

A second method, known as the principal numbered-alternate method, allows members of Congress to designate a principal nominee—effectively their first-choice candidate—while ranking alternates in order of preference. If the principal nominee is fully qualified, USNA is required to admit them regardless of their WPM score. However, if the principal declines the offer or fails to meet qualifications, the appointment moves down the list to the next highest-ranked alternate.

Finally, the principal competitive-alternate method is similar to the previous approach but does not require members to rank alternates. If the principal nominee is ineligible or declines the appointment, USNA evaluates the remaining candidates based on their WPM scores and selects the highest-scoring qualified individual.

1.3.2 Service-Connected Nominations

A second category of nominations is service-connected nominations, which are reserved for the children of servicemembers, active-duty Navy or Marine Corps personnel, and members of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). In addition to these groups, the USNA Superintendent is authorized to nominate up to 50 candidates annually.18 While the Superintendent has broad discretion in selecting these nominees and has been described as able to “bring in whoever [he] want[s],” these nominations are most commonly awarded to recruited athletes.19 Even so, they may also be extended to other qualified candidates who have not yet received an admissions offer. In such cases, USNA acknowledges that a candidate’s race may be considered as a “nondeterminative factor” in the decision-making process.20 At the same time, it asserts that race has not been a factor in these decisions since 2009.21 However, that this claim rests on the anecdotal recollections of the Dean of Admissions rather than a documented policy change does not instill much confidence.

1.4 Selection and Capacity Constraints

1.4.1 Class Size and Competitive Pool

On average, 5,088 domestic applicants submitted complete applications annually during the 2023–2027 admission cycles, out of an average total of 14,102 applications submitted each year.22 After excluding foreign applicants, those deemed medically or physically unqualified, and those without a nomination, the effective applicant pool averages 3,098 per year.23 By law, the total USNA student body (the “Brigade of Midshipmen”) is capped at 4,400 midshipmen across all four years, with each incoming class typically comprising just under 1,200 individuals.24 Thus, in each of the five admission cycles, an average of 3,098 applicants competed to fill approximately 1,200 available admission slots.

1.4.2 Special Admission Categories (Athletes and Prep Applicants)

In practice, however, the “true” pool of competition is even smaller, as certain groups enjoy near-automatic admission. Most notably, Blue Chip Athletes (BCAs) face almost no real competition for admission. Of the 1,268 BCA applicants during the 2023–2027 admission cycles, all but two were admitted—yielding an acceptance rate of 99.8%.25 BCAs typically account for about one-fifth of each incoming class.26

A similar dynamic exists for candidates admitted through the Naval Academy Preparatory School (NAPS) and other USNA-affiliated private prep programs—an admissions pathway explored in more detail later. Nearly all NAPS candidates who meet minimum academic and physical qualifications ultimately receive offers to attend USNA, with admission rates of 94.2% for NAPS graduates and 97% for private prep program graduates during the same period.27 Excluding those who are also BCAs, prep school applicants constituted approximately 13% of all USNA admits for the Classes of 2023–2027.28

1.4.3 The STEM Degree Mandate and Academic Priorities

Beyond selection and capacity constraints, USNA is also required to ensure that at least 65% of each graduating class earns a technical degree in fields such as engineering, mathematics, or the physical sciences.29 While this mandate applies to graduation rather than admissions, it directly influences the selection process by incentivizing the admission of candidates with strong academic performance in STEM disciplines. Applicants with high standardized test scores in math and science, advanced coursework in these subjects, or demonstrated aptitude in technical fields are often prioritized to help ensure the academy meets its STEM quota. As a result, this requirement further narrows the competitive applicant pool by effectively raising the academic bar for non-STEM candidates.

1.5 Admission Pathways for Nominated Candidates

1.5.1 Pathways for Congressional Nominees

While more than 80% of those admitted to USNA during the 2023–2027 class cycles were Congressional nominees, fewer than half (49.4%) secured their place by winning a Congressional slate.30 For nominees who do not win their slate, there are two primary pathways to admission. The first is through the Qualified Alternates (QA) system, which allows up to 150 (recently extended to 200) Congressional nominees per admissions cycle to receive appointments.31 By statute, these QAs are selected based on their Whole Person Multiple (WPM) scores, with appointments ostensibly granted to the top 150 non-slate-winning Congressional nominees. USNA claims that these selections are made solely on the basis of WPM scores, leaving no room for discretion or the consideration of race.32 However, as later sections will demonstrate, USNA appears to have greater latitude in these decisions than it publicly reveals.

If not selected as a QA, and provided that “vacancies in the incoming class of midshipmen remain following all the appointments authorized by law,” a Congressional nominee may still gain admission as an Additional Appointee (AA).33 During the 2023–2027 admissions cycles, an average of 266 candidates per year were admitted as AAs.34 Unlike QAs, AA appointments are not determined strictly by WPM scores. Instead, USNA describes AA selection as being based on “a holistic assessment of candidates who are expected to make valuable contributions to the brigade environment.”35 While broadly defined, this assessment may include factors such as leadership potential, extracurricular involvement, and other subjective qualities. USNA further acknowledges that race or ethnicity may be one of many nondeterminative factors considered in AA appointments.36

If neither admitted as a QA nor AA, a final, albeit indirect, path to USNA is through an offer of admission to a Naval Academy preparatory program, the largest of which is the Naval Academy Preparatory School (NAPS). NAPS accounted for 80% of all prep admits during the 2023–2027 admission cycles.37 Generally, prep school offers are extended to applicants who, by USNA’s assessment, demonstrate leadership potential and physical fitness but require additional academic preparation before gaining admission.38 Although WPM scores are not formally used in selecting prep school candidates, academic deficiencies often factor into the decision to offer a prep pathway.39

Unlike direct USNA admissions, securing a nomination is not a prerequisite for prep school admission. This gives USNA greater discretion in determining who receives prep school offers, as nominations do not restrict or dictate selections. However, according to USNA, priority is typically given to enlisted sailors and Marines, as well as recruited athletes.40 Conditional on meeting minimum academic and fitness performance requirements—including maintaining a cumulative GPA of 2.0 (a threshold lowered from 2.2 prior to the 2019–2020 academic year41)—just over 94% of those admitted to NAPS are subsequently admitted to USNA in the following admissions cycle, regardless of their initial WPM score.42

1.5.2 Pathways for Service-Connected Nominees

Service-connected nominees accounted for nearly 15% of all USNA admits during the 2023–2027 admission cycles.43 However, over 60% of these candidates did not secure a service-connected slate and were instead admitted through a USNA prep program. Within this subgroup, approximately 30% initially failed to secure any type of nomination when first applying to USNA. The remainder consisted of candidates who held service-connected nominations but were deemed academically unprepared for direct admission.44

Importantly, nominations from one USNA admission cycle do not carry over to the next. As a result, prep admits must reapply for a nomination and are encouraged to seek endorsements from all available sources when applying to USNA.45 Consequently, a candidate who was admitted to a prep program as a Congressional nominee may ultimately matriculate into USNA as a service-connected nominee in the following cycle.

Overall, approximately 43% of those who entered USNA from a prep program during the 2023–2027 class cycles were admitted as service-connected nominees.46 The remainder were admitted through Congressional channels, including a non-trivial subset who secured Congressional slate wins. This further underscores the flexibility USNA exercises in the assignment of admission charges—a topic I turn to shortly.

1.6 USNA’s Stated Use of Race in Admissions

USNA openly acknowledges considering applicants’ race or ethnicity in certain admissions decisions. As noted in previous sections, it explicitly concedes that race may be a factor in (a) deciding Congressional slate winners through the Slate Review Committee (SRC), particularly when candidates’ WPM scores are within a certain threshold and the lower-scoring candidate is selected; (b) awarding Additional Appointee (AA) appointments; and (c) issuing Superintendent nominations—though, according to the Dean of Admissions, race has not been a factor in these since 2009.

In addition, USNA acknowledges considering race when conferring Letters of Assurance (LOAs)—early but conditional offers of admission that are contingent on completing the application process and meeting medical and physical qualifications.47 While LOAs are typically extended to candidates with WPM scores exceeding 70,000, they may also be granted to lower-scoring applicants who demonstrate qualities that USNA deems valuable. Such qualities include, but are not limited to, “unusual life experience” and “overcoming significant hardship or adversity.”48 USNA explicitly states that race or ethnic background may also be considered, though purportedly as only one factor among others.49 Because 84% of admitted candidates during the 2023–2027 admission cycles were recommended for LOAs by the admissions board, these recommendations play a decisive role in shaping the composition of each incoming class.50

Trial proceedings revealed an additional avenue through which race may influence admissions decisions: waitlist selections. Although USNA did not publicly disclose this practice before litigation, it admitted in court that race can, at least occasionally, be a factor in deciding whether to take a candidate off the waitlist and extend an offer of admission.51

While acknowledging that race factors into the foregoing areas of the admissions process, USNA repeatedly insists that this consideration is “limited,” “non-determinative,” and always part of a “holistic assessment that takes into account all aspects of an applicant’s file”.52 It maintains that no candidate is admitted “solely because of their race” and contends that, due to the congressional nomination process and WPM scoring, “race is not considered at all for many appointments to the Academy.”53

Yet despite these assertions, USNA simultaneously claims to have no insight into what the racial composition of its classes would look like absent the consideration of race. By its own admission, it has never conducted modeling to explore this question and offers no clear explanation for why such an analysis has not been undertaken.54 At the same time, USNA argues that eliminating racial considerations would cause minority enrollment to “drop dramatically,” a claim that stands in tension with its characterization of race as a minor and non-determinative factor in admissions.55

This raises an important question: If USNA has never assessed how race affects admissions outcomes, how can it confidently claim that its role is ‘limited’ and ‘non-determinative’? And if race is truly marginal, why does USNA anticipate a drastic demographic shift without it?

To further complicate matters, testimony from USNA’s key trial witnesses regarding the role of race in the admissions process was at times unclear, if not outright contradictory. When questioned by USNA’s defense lawyers, the academy’s director of nominations and appointments stated that the admissions board does not consider race when determining whether candidates are “qualified” or “not qualified.”56 Yet under cross-examination by an SFFA attorney, she acknowledged that “ethnic heritage, racial or ethnic diversity” could be among the factors considered in qualification determinations.57 This was later corroborated by a member of USNA’s admissions board, who, when asked whether “race can be used to determine whether a candidate is qualified,” answered in the affirmative.58

1.7 Flexibility in the Admissions Process

USNA’s admissions process is far more flexible—and discretionary—than the academy publicly acknowledges. One major source of this flexibility is the substantial number of applicants who secure nominations from multiple sources, which allows USNA to shift candidates between different admission channels. In addition, USNA enjoys considerable latitude in selecting replacements for slate winners who decline offers or are ultimately deemed unqualified.

For example, consider a candidate who is the third alternate on a district’s Congressional slate but also the principal nominee on a Senatorial slate. If the top two alternates on the Congressional slate decline admission offers, USNA can declare this candidate the district slate winner. This, in turn, leaves the Senate vacancy open, allowing USNA to fill it with a lower-scoring candidate who would not have qualified for a QA slot.

A similar dynamic occurs with “competitive” slates or when principals on “principal competitive-alternate” slates decline offers or fail to meet qualifications. In theory, a qualified candidate with a WPM score exceeding the second-highest scorer by more than 4,000 points should win these slates.59 However, if this top candidate also qualifies for QA admission, and the second-highest scorer does not meet the QA threshold, USNA may assign the top candidate to a QA slot and award the Congressional slate to the lower-scoring nominee.

More broadly, discovery evidence suggest that when a slate winner declines an offer, USNA is not bound by WPM rankings in selecting a replacement. This means a lower-scoring candidate may be chosen over more qualified applicants. Evidence introduced at trial further indicates that race sometimes influences these replacement decisions. For instance, during the discovery process, SFFA obtained emails listing potential replacements for slate winners who had declined admission, where race or ethnicity was prominently featured as a primary identifying characteristic.60

There are also numerous cases in which NAPS applicants (i.e., those applying to USNA from NAPS) win Congressional slates over higher-scoring competitors.61 This is surprising not only given the generally low WPM scores of NAPS applicants but also because it occurs even in admission cycles where WPM scores for NAPS candidates are not reported in the data. This further calls into question the transparency of USNA’s admissions process, particularly the extent to which WPM rankings genuinely drive slate outcomes.

Taken together, these factors cast serious doubt on USNA’s claim that race plays only a minor role in admissions. The academy’s own admissions process—steeped in discretion—creates ample opportunities for racial considerations to influence outcomes at multiple stages. And we don’t have to take USNA at its word. Thanks to trial disclosures and the analysis conducted by SFFA’s expert witness, Peter Arcidiacono, the data tell the real story.

2. Review of Findings from SFFA’s Analysis of USNA Data

As part of the discovery process in this case, USNA was ordered to provide SFFA with applicant files and admissions data for all individuals who applied during the admissions cycles for the Classes of 2023–2027. These data were analyzed by Duke University economist Peter Arcidiacono, who was retained by SFFA and has conducted similar statistical analyses in its (ultimately successful) challenges to affirmative action policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina.

Arcidiacono’s primary task was to answer the question that USNA was unwilling to quantify: To what extent does race/ethnicity influence admissions decisions at USNA and NAPS? While USNA acknowledges using race in a “limited” and “non-determinative” fashion in certain areas of the admissions process, the actual scope and impact of these considerations remained unclear. Arcidiacono’s analysis systematically evaluates these claims and quantifies the extent to which race affects admissions outcomes.

The following section reviews the key findings from this analysis and their implications for USNA’s admissions policies and practices.

2.1 Overall Admission Rates

Applicants from NAPS and other USNA-affiliated prep programs are virtually guaranteed admission to the next incoming USNA class, provided they meet minimal performance requirements. Thus, with few exceptions, admission to a prep program effectively ensures admission to USNA. Accordingly, Arcidiacono’s analysis begins with descriptive statistics outlining the rates at which applicants are offered admission to either USNA or a prep program, broken down by race and ethnicity. These data are visualized in Figure 2.1A below.

Figure 2.1A. Admission Rates to USNA and USNA-Affiliated Prep Programs by Race/Ethnicity, Regardless of Nomination Status.

Note. Bars represent the percentage of applicants who received an offer of admission to either USNA or a USNA-affiliated prep program. Sample restricted to domestic applicants who submitted complete applications and passed the fitness and medical exams. Data correspond to applicants for the USNA Classes of 2023–2027. Sample sizes are reported in parentheses.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 218, Table 3.6, at 31.

As shown, White applicants (44.1%) and those who declined to specify their racial background (38.9%) were the only subgroups with overall admission rates below 50%. By contrast, Black applicants had the highest offer rate at 77.9%, followed by Native American/Hawaiian applicants (61.5%), Asian applicants (61.1%), and Hispanic applicants (56.5%).

While these disparities are striking, they do not, in and of themselves, constitute definitive evidence of racial preferences. One reason is that some applicant pools are significantly more advantaged in the admissions process than others. Recall that Blue Chip Athletes (BCAs) are virtually guaranteed admission. Consequently, racial groups with disproportionately high numbers of BCAs may appear to benefit from racial preferences when, in reality, their elevated admission rates stem, at least in part, from athletic recruitment. Similarly, groups with higher proportions of prep school applicants will also exhibit inflated admission rates, as applying from a prep school—though less advantageous than being a BCA—still significantly increases the likelihood of admission.

Figure 2.1B. Distribution of Applicant Pools by Race Among USNA Admits

Note. Sample sizes reported in parentheses. Sample includes only applicants admitted to USNA. “BCA” refers to Blue Chip Athletes, while “Prep” refers to those admitted to USNA from the Naval Academy Preparatory School (NAPS) or another USNA-affiliated private prep program.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 218, Table 3.8, Panel B, at 35.

Figure 2.1B above helps illustrate this dynamic by showing how admitted students from each of the four major racial groups are distributed across different applicant pools. Black admits provide the clearest example of a group whose admission rates are inflated due to their disproportionate representation among BCAs and prep school applicants. Approximately 60% of Black admits were either BCAs or prep school applicants, compared to just 29% of White admits. However, the share of BCA and prep school applicants among Hispanic (35%) and Native American/Hawaiian admits (35%) was only slightly higher than among White admits, while the share among Asian admits was even lower. Therefore, the elevated admission rates for these three minority groups cannot be solely attributed to BCA or prep school pathways. As we will see, even after accounting for these factors, Black applicants continue to enjoy significantly higher admission rates than similarly qualified applicants of other racial groups.

2.2 Admission Rates to USNA

Given that the presence of BCA and prep school applicants can confound assessments of racial preferences in admissions, a more accurate analysis requires excluding these groups. This is reflected in Figure 2.2A, which presents admission rates for each racial group across three applicant pools: all applicants, applicants excluding BCAs, and applicants excluding both BCAs and prep school candidates. In the latter group, admission rates are relatively consistent across racial groups—with one notable exception: Asian applicants are admitted at a significantly higher rate (54.8%) than all others. Differences between White (36.1%), Black (37.3%), and Hispanic (35.9%) applicants are modest and not statistically significant.

Figure 2.2A. Admission Rates to USNA by Race and Applicant Pool

Note. Bars represent the percentage of applicants who received an offer of admission to USNA, disaggregated by applicant pool and race/ethnicity. The sample is restricted to domestic, complete applications that received a nomination and passed both the fitness and medical exams. Sample sizes for each racial/ethnic group are shown in the legend, while total sample sizes for each applicant pool are listed next to the corresponding labels.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 218, Table 3.7, at 33.

It would be a mistake, however, to interpret this relative parity as evidence that racial preferences in USNA admissions are minimal or non-existent. Such a conclusion assumes that applicants within each racial group are relatively equal across variables that significantly influence admission decisions. As shown in Figure 2.2B, this assumption does not hold. Among non-BCA/non-Prep applicants, Black admits score significantly lower than their White counterparts across all components of the WPM, including standardized test scores, class rank, and extracurricular evaluations. On several metrics—such as SAT scores—Black admits even score lower than or are comparable to White applicants who were denied admission to USNA. To a lesser extent, Hispanic admits also score lower than White admits on every metric included here, though they tend to receive somewhat higher RAB adjustments (not shown). Asian admits, meanwhile, outperform or match White admits on academic components of the WPM (e.g., SAT scores and class rank), as well as on the overall WPM. However, they tend to score significantly lower in areas such as athletic extracurricular involvement (Athletic Scores) and physical fitness (CFA Scores).

Figure 2.2B. Application Summary Statistics by Race, Removing BCAs and Prep Pool

Note. Sample (N=12,304; White N=8,022; Black N=778; Hispanic N=1,551; Asian N=1,444) restricted to domestic, complete applications that received a nomination and passed the fitness and medical exams. Athletic and Non-Athletic Scores measure extracurricular involvement in athletic and non-athletic activities, respectively. RSO Scores reflect character ratings from applicants’ high school math and English teachers. CFA Scores measure Candidate Fitness Assessment performance. Combined WPM Scores are a weighted composite of all listed factors except CFA Scores. Dashed horizontal lines indicate the average scores for admitted applicants.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 218, Table 3.16, at 47.

More compelling evidence of the extent of racial preferences emerges when examining admission rates by WPM decile, as shown in the right panel of Figure 2.2C. In general, racial preferences—particularly for Black applicants—are most pronounced in the lower-middle to upper-middle deciles of the WPM distribution, with disparities diminishing at the extremes. For instance, in the first decile, admit rates are similarly low across all racial/ethnic groups: 3.1% for White applicants, 4% for Black applicants, 3% for Hispanic applicants, and 4.7% for Asian applicants. However, by the 5th decile, the admit rates diverge sharply: 20.1% for White applicants, compared to 59.7% for Black applicants, 29.7% for Hispanic applicants, and 38.2% for Asian applicants.

Figure 2.2C. Racial Group Shares (Left) and Admission Rates (Right) by WPM-23 Decile, Excluding BCAs and Prep Applicants

Note. Sample restricted to non-Blue-Chip, non-Prep-Pool, domestic, complete applications that received a nomination and passed the fitness and medical exams, and that have a valid WPM Score. Sample sizes are reported in parentheses. Deciles are computed separately for each class year. WPM-23 refers to the raw WPM score (excluding RAB points), calculated using the 2023–2024 component weights for all admission cycles.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 218, Tables 3.19–3.20, at 50–51.

The scale of preferences for Black applicants becomes even more evident when comparing admission rates across deciles. For example, Black applicants in the 4th decile (47%) are admitted at a slightly higher rate than White applicants in the 8th decile (46.6%), despite being four deciles lower in the WPM distribution. By the 9th decile, admission rates across groups begin to converge, but significant disparities remain. White applicants in this decile have a 66% chance of admission, compared to 90.3% for Black applicants, 83.6% for Hispanic applicants, and 87% for Asian applicants.

A main reason why preferences tend to be strongest for Black applicants is reflected in the left panel of Figure 2.2C, which plots the racial group shares of each decile. Specifically, nearly two-thirds (65.8%) of non-BCA/non-prep Black applicants are concentrated in the bottom four deciles, compared to 46.7% of Hispanic, 31.6% of White, and 26.2% of Asian applicants. In contrast, just 17% of Black applicants place in the top four deciles, compared to 32.2% of Hispanic, 48.2% of White, and 52.7% of Asian applicants.

Given these distributions, a race-blind admissions system that selected all applicants from the top four WPM deciles would yield a markedly different racial composition among admitted students. Under such a system, the share of non-BCA/non-prep admits would shift to 71.4% White (compared to 61.3% in actuality), 14.3% Asian (16.7%), 8.5% Hispanic (11.8%), and just 1.9% Black (6.1%). If applied to the entire qualified applicant pool—meaning BCAs and prep applicants would no longer be virtual admission shoo-ins—Whites would constitute 70.4% of admits (compared to 58.7% in actuality), Asians 13.8% (14.3%), Hispanics 9.3% (12.5%), and Blacks 2.7% (10.5%).

Ultimately, USNA would be unable to increase Black—and, to a lesser extent, Hispanic—representation to levels even approaching their share of the U.S. population if all applicants were held to the same standards as White applicants. There are simply too few Black applicants in the top deciles for race-neutral policies to achieve this outcome. Even with racial preferences, Black applicants remain underrepresented among admits.

This imbalance—along with the smaller proportion of Hispanic applicants in the top deciles relative to Whites and Asians—may also explain why substantial racial preferences are extended to Asian applicants, despite their overrepresentation among admits relative to their share of the wider population. If USNA cannot achieve representational parity for each minority group individually, it can at least seek parity in the broader “non-White vs. White” sense--a metric it regularly tracks.62

2.3 Modeling Racial Preferences in USNA Admissions

While Arcidiacono’s analysis has demonstrated that admission rates for non-BCA/non-Prep applicants vary significantly by race within the same WPM decile, the extent to which these disparities persist after accounting for additional factors remains an open question. To address this, Arcidiacono employs a series of eight logistic regression models, each progressively incorporating more control variables.

The results of these models are presented in Figure 2.3A, where the bars represent logit coefficients, indicating differences in the log odds of admission relative to White applicants. Each model includes a progressively richer set of controls, with Model 1 adjusting only for sex and class year. As in Figure 2.2A, this initial model shows that Asian applicants are more likely to be admitted than White applicants, while Black and Hispanic applicants are admitted at roughly similar rates. Female applicants (not shown) also receive a modest admissions boost relative to males, though the gap is smaller than that observed between Asian and White applicants.

Figure 2.3A. Logit Estimates of USNA Admissions, Excluding BCAs and Prep Applicants

Note. Bars represent logit coefficients, with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals. In each panel, error bars that cross the dashed vertical line are not statistically significant at the 95% confidence threshold. Model sample sizes are reported in parentheses. Four observations with missing CFA scores are dropped from Model 3 onward. Model 8 further restricts the sample to observations with no missing values for household income, private high school attendance, or the percentage of the applicant’s high school cohort attending a four-year college.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Rebuttal Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 222, Table 4.1R, at A21.

As additional controls are introduced, the coefficients for each racial group increase in magnitude. For instance, Model 3 accounts for first-generation college status, household income, and community-level socioeconomic indicators (e.g., the percentage of an applicant’s zip code eligible for free or reduced-price lunch and the average salary in the zip code). It also controls for individual WPM components (excluding RAB points) and CFA scores. After these adjustments, the coefficient for Black applicants jumps from 0.025 in Model 1 to 1.981, for Hispanic applicants from -0.020 to 0.839, and for Asian applicants from 0.720 to 0.955.

The next major increases in coefficients occur in Model 5, which incorporates interactions between WPM components and class year to account for changes in the WPM weighting formula introduced in the Class of 2025 admissions cycle. It also adjusts for slate characteristics, including the number of available vacancies, the method of nomination, the number of nominees, average WPM scores, and the distance between a nominee’s WPM and the top score on the slate. These controls capture differences in slate types (e.g., principal numbered-alternate vs. competitive) and the degree of competition faced by applicants. After accounting for these factors, the estimated racial preference for Black applicants rises sharply to nearly 3.0 (2.924), while the coefficients for Hispanic and Asian applicants also increase (1.117 and 1.405, respectively).

Adding BGO interview scores, legacy status (e.g., family members who attended USNA or another service academy), and RAB points for AP, IB, and honors coursework in Model 6 has virtually no effect on these coefficients. Further controlling for total RAB points in Model 7 leads to a slight increase in the coefficient for Black applicants (3.077) while leaving estimates for other racial groups largely unchanged.

Finally, Model 8 restricts the sample to applicants with complete data for household and community socioeconomic indicators, reducing the sample size by 38%. This adjustment accounts for missing data that disproportionately affect Black applicants and may otherwise overstate their socioeconomic advantage. As a result, the Black coefficient rises further to 3.7, while coefficients for other racial groups see only modest increases.

These results underscore a critical point: the apparent racial parity in baseline admission rates masks substantial disparities in applicant qualifications. When qualifications are statistically equalized, the magnitude of racial preferences in USNA admissions—particularly for Black applicants—becomes strikingly clear. Moreover, the fact that these estimates increase as additional control variables are introduced suggests that the preferences are even stronger than they initially appear. The models explain a significant share of admissions variability (Pseudo R² values of 0.537 and 0.561 for Models 7 and 8), reinforcing the robustness of these findings.63

This robustness is also directly at odds with USNA’s rebuttal, which claims that Arcidiacono’s estimates are inflated due to omitted variable bias. To the contrary, as later sections will discuss, omitted variables do not appear to drive these results. If anything, these estimates are likely conservative, given that the models account for a broad range of applicant characteristics yet still reveal striking racial disparities in admissions outcomes.

2.4 Quantifying Racial Preferences in Practical Terms

At this point, a casual reader or someone less familiar with statistical analysis might wonder: what do the preceding logit coefficients actually mean in practical terms?

One way to illustrate the real-world impact of these estimates is to assess how a White applicant’s admission probability would change if they were evaluated as a member of a different racial group. Professor Arcidiacono conducts such an analysis using the estimates from Model 6 in Figure 2.3A, which he refers to as his “preferred model”.64 To estimate these probabilities, Arcidiacono applies the logistic transformation to the model coefficients, adjusting the applicants’ race while holding all other variables constant.65 This analysis is performed for all class years combined (the “pooled” model) and separately for applicants to the 2023–2024 and 2025–2027 admission cycles to changes to the WPM formula.

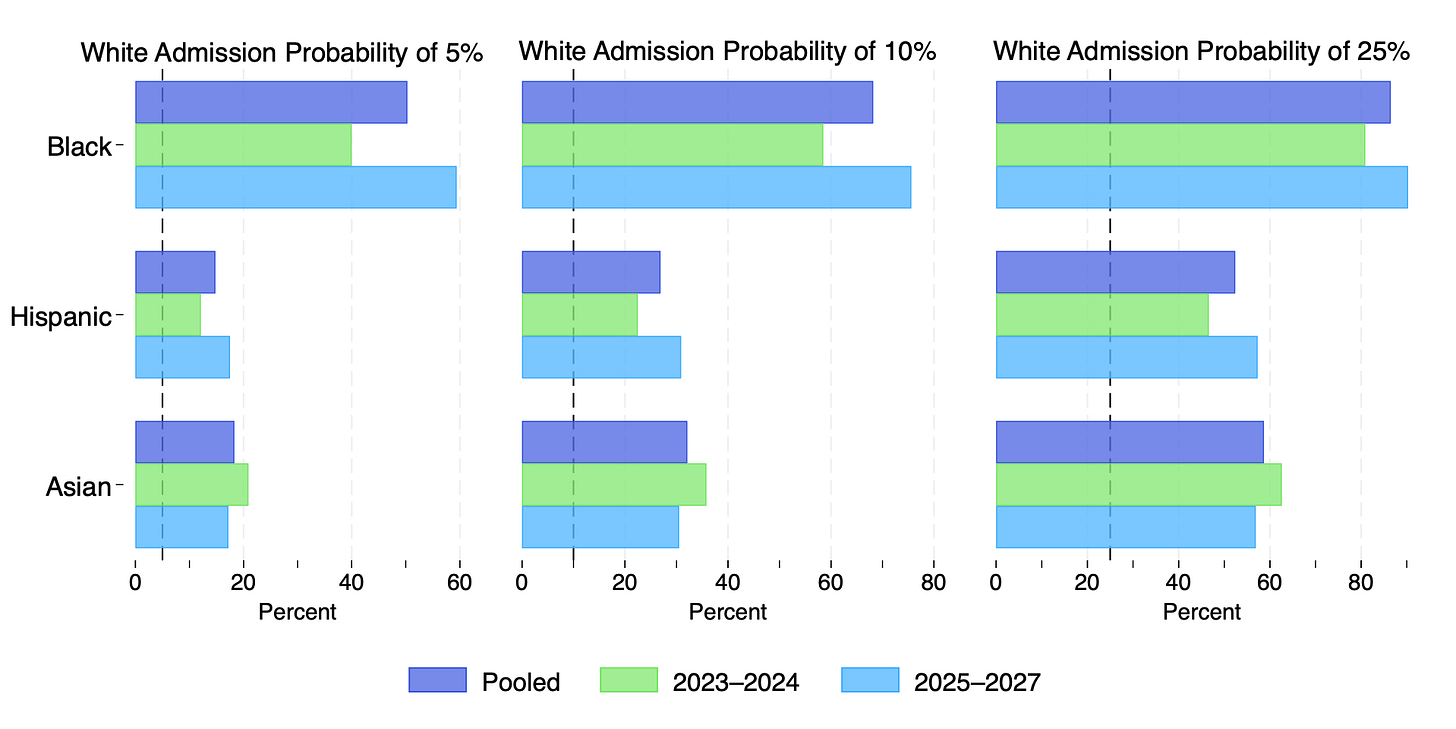

The results, shown in Figure 2.4A below, translate abstract statistical coefficients into real differences in admission odds. Beginning with the pooled models (dark blue bars) in the top row, Professor Arcidiacono estimates that a White applicant with a modest 5% probability of admission would have a 50.3% chance of admission if treated as Black, a 14.8% chance if treated as Hispanic, an 18.3% chance if treated as Asian, and a 15.3% chance if treated as Native American/Hawaiian. Notably, the admission ‘bonus’ for being treated as a black applicant increased from 40% in the 2023–2024 cycle to 59.4% in the 2025–2027 cycle. This latter period coincided, perhaps not coincidentally, with heightened public focus on racial equity following the killing of George Floyd. Turning to the right panel, a White applicant with a 25% chance of admission would see their probability rise to 85.7% if treated as Black, 51.3% if treated as Hispanic, and 59.1% if treated as Asian.

Figure 2.4A. Estimated Admission Probability of a White Applicant if Treated as a Different Race

Note. Bars represent estimated admission probabilities for White applicants if treated as a different racial group, based on Model 6 from Figure 2.3A. Estimates are presented for all five class years combined (pooled model) and separately for the 2023–2024 and 2025–2027 admissions cycles. Dashed vertical lines denote the different White admission probabilities.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Rebuttal Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 222, at A22.

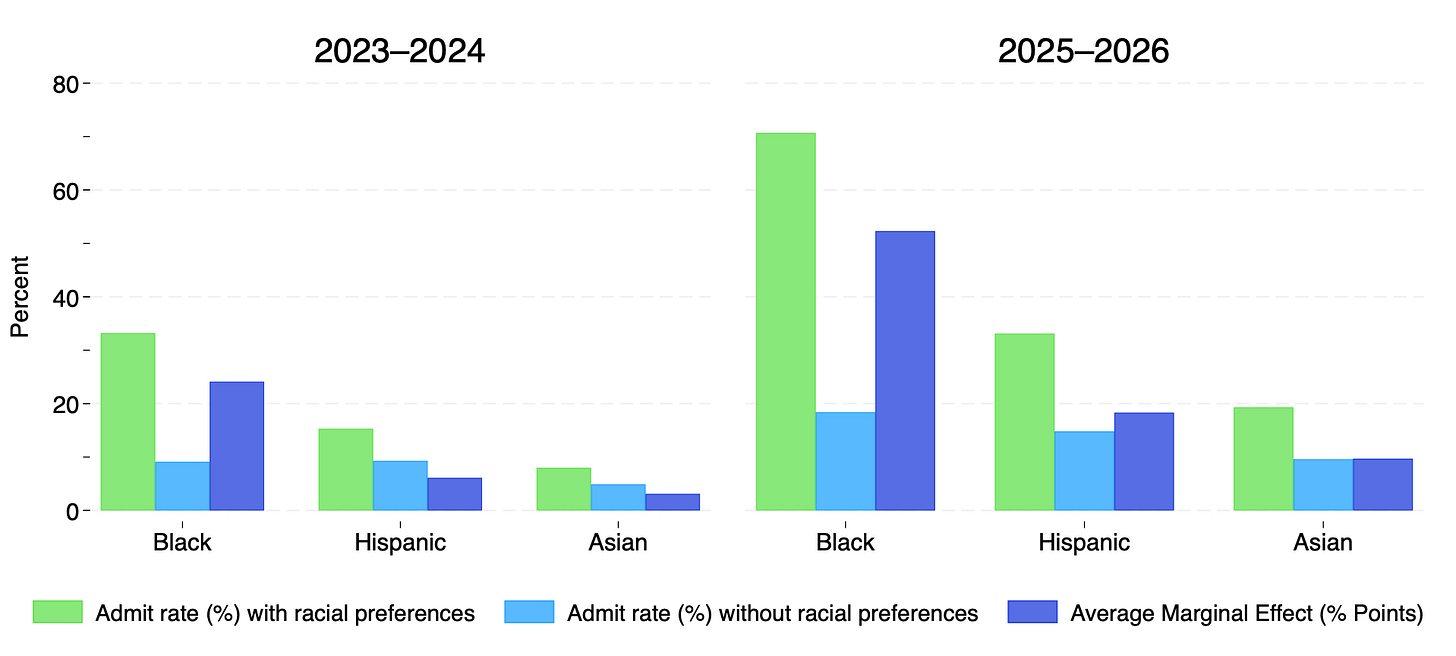

Another way to quantify racial preferences is to estimate how admission probabilities would change if all applicants were evaluated under the same criteria as White applicants. To this end, and again using estimates from his preferred model, Professor Arcidiacono calculates the average marginal effects for each group. These represent the difference between the average admission probability for a member of a given racial group and the average admission probability for a White applicant, effectively isolating the role of racial preferences in determining admission outcomes.

Figure 2.4B presents these results. Across all five admission cycles, Black applicants would see their average admission probability drop by 24.3 percentage points, from 37.4% to 13.1%, if held to the same standards as White applicants. Similarly, the average Hispanic applicant would experience an 11.1-point reduction (35.9% to 24.8%), and the average Asian applicant would see a 17.6-point reduction (54.8% to 37.2%). Once again, the estimated drop in admission odds for Black applicants is larger in 2025–2027 (-29 points) than in 2023–2024 (-18.6 points). It also more than doubled in size for Hispanic applicants between these periods, from -7 points in 2023-2024 to -14.5 points in 2025–2027.

Figure 2.4B. Estimated Change in Admission Probabilities if Applicants Were Evaluated as White

Note. Bars represent the estimated change in average admission probability for each racial group if evaluated under the same criteria as White applicants, based on Model 6 from Figure 2.3A. Dark blue bars indicate the actual admission rate with racial preferences, green bars represent the estimated admission rate without racial preferences, and light blue bars denote the average marginal effect (AME), or the difference between the two. Estimates are presented for all five admission cycles combined and separately for the 2023–2024 and 2025–2027 cycles.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Rebuttal Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 222, at A23.

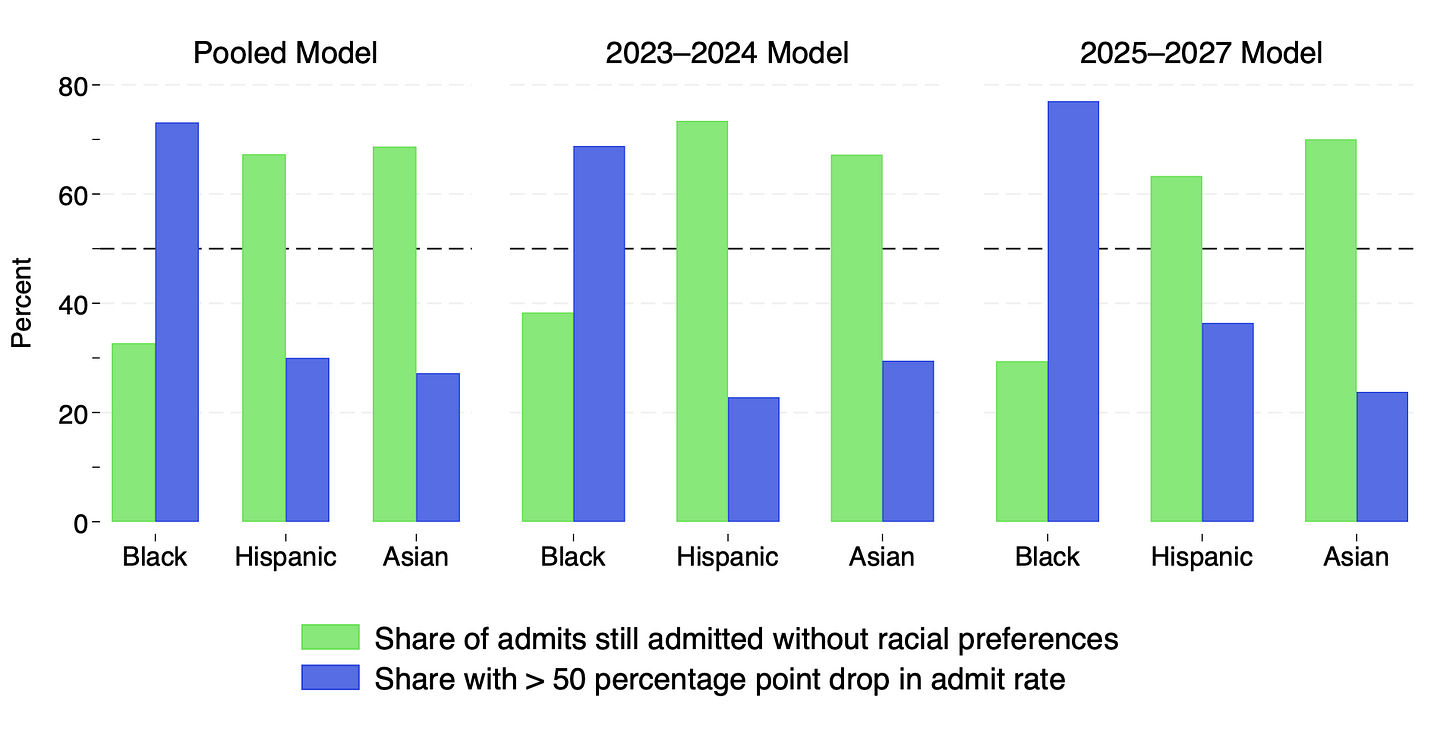

Still another way of demonstrating the practical effects of racial preferences is to consider how many admits who benefited from racial preferences would still have been admitted in their absence. Professor Arcidiacono tackles this question using a Bayesian framework, which leverages the estimated admissions model to calculate admission probabilities both with and without racial preferences. By comparing these probabilities, the analysis accounts for observed characteristics and adjusts for the unobserved traits that likely played a role in securing admission under the status quo. This approach offers a clearer estimate of how many admits depended on racial preferences to secure admission.

Results for this analysis are graphed in Figure 2.4C. Most striking are the findings for Black admits, only 33.2% of whom, on average across the five admission cycles, would have been admitted in the absence of racial preferences. As shown by the blue bars, this represents a more than 50% reduction in admission odds for a staggering 73% of Black admits—a figure that rises to 78.1% during the 2025–2027 period. In contrast, clear majorities of admits from the other three racial groups would still have gained admission even without the benefit of racial preferences. However, their numbers would decline by approximately a third, with 68% to 70% of Hispanic and Asian admits “surviving” the removal of preferences.

Figure 2.4C. Estimated Probability of Admission for Previously Admitted Applicants if Racial Preferences Were Removed

Note. Bars represent the estimated share of previously admitted applicants who would still have been admitted under a race-neutral model. Estimates are based on Bayesian posterior probabilities derived from Model 6 in Figure 2.3A. Green bars indicate the share of admits who would still gain admission without racial preferences, while dark blue bars represent the share of admits whose admission probability would drop by more than 50% under a race-neutral model. Estimates are presented separately for all five admission cycles combined, as well as for the 2023–2024 and 2025–2027 cycles.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Rebuttal Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 222, at A24.

2.5 Racial Preferences Across Admissions Channels

To this point, Professor Arcidiacono’s analyses have quantified racial preferences in USNA admissions as a whole, without examining how these preferences vary across the distinct admission channels discussed in Section 1. His next analysis addresses this gap by employing a nested logit model, which estimates the probability of earning admission through one channel relative to another. This method accounts for the fact that candidates do not apply separately to each pathway but instead are sorted into different categories by USNA. As such, it allows for a more precise examination of how racial preferences might differentially impact decisions across pathways, such as winning a Congressional slate, being selected as a Qualified Alternate (QA) or Additional Appointee (AA), or securing admission as a service-connected nominee.

Figure 2.5A visualizes the logit coefficients for each non-White racial group, derived from four related models adjusted for all control variables in Professor Arcidiacono’s preferred specification. The first model, limited to Congressional nominees with WPM scores above the 150th-ranked QA cutoff, examines the likelihood of being selected as a QA versus winning a Congressional slate. Notably, the only statistically significant coefficient is for Black nominees, who have a substantial coefficient of 0.893. This finding is surprising given that QAs are ostensibly selected from the highest WPM-scoring Congressional nominees who fail to win a slate—yet Black applicants consistently have the lowest average WPM scores across all admission channels.66

Figure 2.5A. Nested Logit Estimates by Admission Channel

Note. Bars represent logit coefficients, with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals. Error bars that cross the dashed vertical line are not statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. All models exclude Blue Chip Athletes and applicants from the Prep Pool. Sample sizes are as follows: 2,008 for the Qualified Alternate model, 941 for the Additional Appointee model, 10,743 for the Congressional Slate Winner model, and 1,536 for the Service-Connected model.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Rebuttal Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 222, Table D.86R, at D88.

A second model, consisting of Congressional nominees with WPM scores below the 150th-ranked QA cutoff (rendering them ineligible for QA appointments), estimates the odds of being admitted as an Additional Appointee (AA) versus winning a Congressional slate. Recall that USNA explicitly acknowledges that race and ethnicity may be considered “as part of a holistic consideration of a candidate” when making AA selections. Unsurprisingly, the coefficients for Asian (1.103), Black (2.216), and Hispanic (1.063) nominees in this model are all positive and substantial, reflecting the influence of racial preferences in this admission channel.

A third model includes all Congressional nominees and examines the odds of winning a Congressional slate versus being denied admission altogether. As its results largely mirror those from Model 6 of Figure 2.3A—with substantial coefficients for each group, though slightly smaller, reflecting the stronger preferences observed in the QA and AA channels—I proceed directly to the fourth and final model. This model estimates the odds of earning admission as a service-connected nominee relative to being rejected. Here, too, the coefficients for each racial group are positive, statistically significant, and varyingly large. Notably, the Black coefficient (2.310) closely resembles that observed in the ‘Congressional Slate Winner vs. No Admission’ model, suggesting that racial preferences for Black applicants are comparably strong across admission channels. In contrast, the coefficients for service-connected Asian (0.600 vs. 1.318) and Hispanic (0.908 vs. 1.091) nominees are considerably and slightly lower than for their Congressional counterparts, respectively.

Before concluding this discussion, I revisit the question of racial preferences in the QA channel, one of the few admissions pathways that USNA explicitly claims to be ‘free’ of racial considerations. This claim hinges on the premise that (medically and physically qualified) Congressional nominees selected as QAs are chosen strictly according to their WPM score rankings. However, there is reason to question USNA’s strict adherence to this rule, as WPM score rankings fluctuate considerably across each admissions cycle.

These fluctuations are largely driven by ‘initial’ QAs either declining admission offers or being designated as winners of Congressional slates, thereby creating openings for lower-ranked candidates. For instance, during the most recent admissions cycle in the data (2027), provisional QA lists obtained by SFFA show that the QA cutoff—the 150th highest WPM score—initially reached 74,851. Yet, the actual observed cutoff was 70,478.67 Further analysis reveals that 74 of the 150 candidates ultimately selected as QAs had WPM scores below the highest provisional cutoff.

One way to assess whether racial preferences influence QA assignments is to compare the racial composition of QA candidates and QA admits who scored above the initial QA threshold with those who scored below it. Figure 2.5B visualizes this comparison, presenting data for QA-eligible candidates across all five admission cycles (left panel) and for candidates from the 2025–2027 cycles (right panel). Above the initial QA threshold, the racial composition of candidates and QA admits closely aligns. Below the threshold, however, this alignment diverges significantly. White applicants comprise just over 72% of all candidates but less than 55% of QA admits, resulting in a QA rate of 27.5%. By contrast, Black, Hispanic, and Asian applicants make up 2.9%, 7.6%, and 13.4% of all candidates but represent 5.7% (QA rate of 70.4%), 9.6% (45.7%), and 26.6% (71.8%) of QA admits, respectively. These disparities are even more pronounced during the 2025–2027 admissions cycles, where the QA rate for White applicants was 31.4%, compared to 85.6% for Black, 63% for Hispanic, and 81.7% for Asian applicants.

Figure 2.5B. Racial Composition of QA Candidates and Admits by Initial QA Cutoff

Note. Sample restricted to applicants eligible for Qualified Alternate (QA) consideration who were not admitted through another channel. To be included, applicants must have exceeded the final QA threshold. Sample sizes for Panel A outcomes are reported in parentheses. Blue and teal bars represent the share of candidates and admits who placed above the initial QA threshold (i.e., the 150th-ranked WPM score), while red, orange, and green bars represent the share of candidates, admits, and admit rates for those below the initial threshold.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 218, Table 4.6, at 74.

Together with the results from the nested logit model, these findings demonstrate that strong racial preferences are present across all USNA admissions channels, including those ostensibly ‘off-limits’ to such considerations. At the same time, they reveal that the magnitude of these preferences varies by racial group and admission channel. Preferences for Black applicants are consistently the largest and relatively uniform across channels. In contrast, preferences for Asian and Hispanic applicants, while smaller overall, show more variation, with stronger effects observed in Congressional channels compared to service-connected ones.

As significant as these preferences are in the direct admission channels, they are even more pronounced for most groups in the indirect ‘prep school’ channel—a topic we turn to next.

2.6 Admissions to NAPS

Up to this point, the analyses have excluded applicants applying from NAPS and other USNA-affiliated prep schools, as these candidates are virtually guaranteed admission to USNA. However, such applicants account for nearly 20% of incoming USNA classes. Any comprehensive audit of racial preferences in USNA admissions would be incomplete—and risk underestimating their scope—if these indirect admission channels were not considered.

As NAPS accounts for more than 80% of all prep admits, and because its medical and physical eligibility requirements align closely with those of USNA, Professor Arcidiacono’s analysis focuses specifically on this program. In addition to being medically and physically qualified, NAPS-eligible applicants must meet three primary criteria: a) they must have been denied direct admission to USNA, b) they must have submitted a complete USNA application, and c) they must not have previously attended or currently be attending another prep program. Recall that securing a nomination is not a prerequisite for admission to NAPS. However, nearly 70% of those admitted during the 2023–2027 admission cycles were, in fact, nominees, reflecting the overlap between NAPS admits and the broader nomination process.68

Notably, prep school admissions are not among the areas in which USNA acknowledges considering race as a factor, suggesting an implicit denial of its use in these decisions.69

The first thing that jumps out in these data is that, regardless of nomination status, most Black applicants who are denied direct admission into USNA are offered admission to NAPS. In fact, Black non-nominees (69.3%) are admitted at significantly higher rates than their nominee counterparts (52.3%). As a result, while Blacks constitute just 8.6% of the total NAPS-eligible sample, they account for 35.2% of all NAPS admits.70 By contrast, White applicants, who comprise 66.6% of eligible applicants, represent only 33.6% of admits—an overall admission rate of just 7.3%. Except for applicants who declined to specify their racial/ethnic backgrounds (7.2%), no other group has a lower overall admit rate. Hispanic applicants are admitted at a rate of 22.2%, Asians at 13.1%, and Native American/Hawaiians at 25.9%.

Figure 2.6A. Admission Rates to NAPS by Race and Nomination Status.

Note. Bars represent the percentage of applicants who received an offer of admission to NAPS, disaggregated by race and nomination status. The sample is restricted to domestic, complete applications that passed the fitness and medical exams, were not admitted directly to USNA, and did not come from the prep pool. Sample sizes for each racial/ethnic group are reported in parentheses next to their labels, while total sample sizes for each applicant pool are listed in the legend.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 218, Table 3.21, at 54.

However, these figures may be misleading for two reasons. First, the sample includes what can be termed ‘latent BCAs’—i.e., athletic recruits who are not yet officially designated as BCAs but who will be assigned that status when they matriculate at USNA the following year. Second, as previously noted, USNA explicitly prioritizes enlisted sailors and Marines for NAPS admissions. Thus, to the extent that black applicants and those from other minority groups are disproportionately represented within these subpopulations, their higher admission rates may partly reflect these institutional priorities rather than exclusively racial preferences.

To address these and other potential sources of bias, Professor Arcidiacono begins by identifying and excluding applicants who are designated as BCAs in the subsequent USNA admissions cycle. Since this adjustment cannot be applied to those admitted to NAPS during the 2027 cycle (due to the absence of 2028 data), the analysis is restricted to the 2023–2026 cycles. Additionally, Professor Arcidiacono employs a series of logistic regression models that control for various factors, including whether applicants received service-connected nominations from the Secretary of the Navy, which are specifically allocated to enlisted Navy and Marine personnel.71

Results from these models, presented as logit coefficients, are plotted in Figure 2.6B. While some controls slightly moderate the coefficients for racial minority groups, these coefficients remain large and statistically significant across all models. For instance, in Model 1—which controls only for sex, first-generation college status, class year fixed effects, and nomination status—the Black coefficient is 2.907. By Model 4, which incorporates all controls from Arcidiacono’s preferred USNA admissions model along with indicators for service-connected nominations, this coefficient declines only marginally, to 2.874. A similar pattern holds for the smaller but still substantial coefficients for other racial groups. Collectively, these results strongly indicate that the large disparities in admission rates observed in Figure 2.6A are indeed driven by racial preferences rather than race-neutral factors.

Figure 2.6B. Logit Estimates of NAPS Admissions

Note. Bars represent logit coefficients, with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals. Error bars that cross the dashed vertical line are not statistically significant at the 95% confidence threshold. Model sample sizes are reported in parentheses. A small number of observations with missing WPM components or CFA scores are dropped from Models 3 onward. The sample excludes Future Blue Chip Athletes, applicants from the Class of 2027 admissions cycle, and those with missing BGO interviews.

Source: Students for Fair Admissions v. The United States Naval Academy, et al., 1:23-cv-02699-RDB, Rebuttal Expert Report of Peter S. Arcidiacono with Appendices, Plaintiff's Exhibit 222, Table 4.7R, at A26.

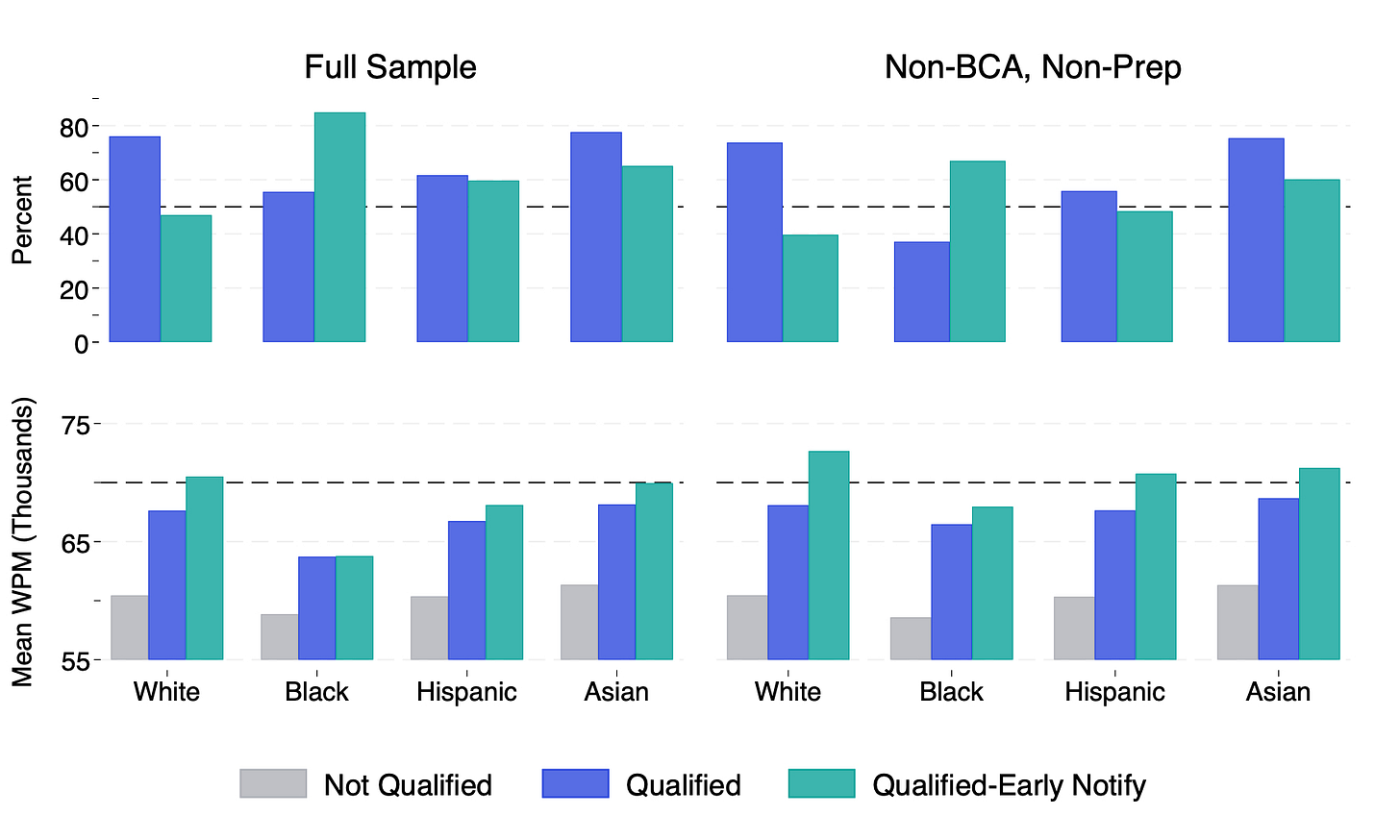

To illustrate the practical effects of these preferences, Professor Arcidiacono employs the same quantification methods used in the earlier USNA admission models. Figure 2.6C, for instance, shows how a White applicant's probability of receiving a NAPS offer would change if treated as a member of another racial group. These estimates are derived from a fifth model, which builds on Model 4 from Figure 2.6B by adding an interaction term between race and an indicator variable for class years 2025 and beyond. This addition is critical, as it reveals that racial preferences in NAPS admissions expanded significantly between the 2023–2024 and 2025–2026 admission cycles. For example, a White applicant with a 5% chance of receiving a NAPS offer would see their probability rise to 37% if treated as Black during the 2023–2024 cycles—and to an astonishing 68% if treated as Black during the 2025–2026 cycles. Similarly, a White applicant with a 25% chance would see their odds rise to 79% during the 2023–2024 cycles and to 93% during the 2025–2026 cycles.

Figure 2.6C. White NAPS Admission Probability (%) if Treated as a Different Race